MAIN BODY

Page 1

Just a few days ago, I landed in Bahrain after finishing off my summer term and first year at the LSE. Done with exams, I was ready for the summer break and, with that in mind, I set off for a fun weekend with my friends involving a movie and lunch at the mall.

After spending a lot of time in London, a metropolitan city that’s lifeblood is its public transport system, it was extremely odd to come back to Bahrain and travel from one destination to another by car. London is a city that is very pedestrian friendly; with numerous crosswalks and large footpaths, it becomes surprisingly easy to walk to any destination, no matter how far away. Over here, signal crossings are very rare, and the few that are available are sparsely located.

Coming from a city in which I was an avid bus user and had the tube map almost memorised, I wanted to do the same in Bahrain. Currently, Bahrain’s public transport system is limited to its recent red bus program which, at first glance, appeared the closest imitation to the London bus system. With promises made of buses running at specific time intervals and routes clearly displayed on the website, I set out to discover for myself how efficient the red bus system was.

With a bus stop right next to my house taking me directly to City Centre, I sat on the bus at 1:40 in the afternoon and reached at two o’clock. The bus arrived a few minutes later than its allotted time but was almost empty throughout the entire journey. Overall, the trip was uneventful, fast and no-hassle; just how a bus journey should be. Coming back, however, it was an entirely different story with the bus taking over an hour later than its assigned time to reach, coming packed with passengers and no announcement or display system informing us of the different stops along the way. It was a messy, inefficient and frustrating ordeal.

In this one experience with the bus system, certain problems stood out. The issue with the bus system is not its inconsistency, its lack of investment in more buses or an effective quality-monitoring system. The problem with the bus system is, perhaps, the connotations it holds in the minds of some Bahraini residents and the attitudes these connotations ferment. Going back to my bus journey, this is extremely evident. Having started my journey in Budaiya, you would expect the passengers in the bus to be an accurate representation of the people that live in the vicinity of the bus stop i.e. a mixture of middle class, working class, expatriate and coming from the many affluent compounds in the neighbouring areas of Saar, Barbar and Jannusan. Instead, the bus was almost empty except for the few labourers returning to Manama or housemaids out for a day off. Whereas, while returning, the journey was filled with many workers coming back after a long day to their homes in the northernmost areas of the island. There was an apparent imbalance, with a public resource being underutilised and overutilized. On the other hand, this may also be reflective of the time and day at which I was travelling; not many people would be going to Manama in the afternoon on a Saturday. Nevertheless, something told me this had nothing to do with the time or day, whether it was morning or afternoon, Saturday or Sunday, it would not have made a difference.

In a report released over nine years ago by the Bahraini Public Commission for the Protection of Marine Resources, Environment and Wildlife, 49% of air pollutants were coming from “transportation methods which have an annual increase rate of 9%”[1]. If we take the annual increase rate to have remained constant, then current air pollutants coming from transportation methods would be at 130%! This does disregard the fact that the percentage of air pollutants coming from transportation would have declined a bit as other air pollution sources rise. However, nonetheless, the fact remains that air

pollution remains a pressing issue in Bahrain, and one only fuelled by the use of inefficient transport. SUVs with only one person, families with multiple cars, vehicles with outdated fuel systems; all these indirectly point towards public transportation as a solution, one that is implemented alongside a severe change in attitudes.

The first solution provided by the Commission itself was to highlight “a huge need to establish an efficient public transportation system”. However, what these policy reports and infrastructure projects can often forget or undermine in the midst of hard data, is that a solution to the environment often involves a more nuanced approach drawing upon the effects of psychological impressions within people’s minds.

The Commission recognises some of this when appreciating the interconnectedness of environmental sustainability with other parts of the economy like the education system and, most importantly, “changing the behaviour of people”. In fact, this is perfectly summed up when the Commission appreciates the need for environmental policies to be “integrated and mainstreamed into the national socio-economic developmental plans”, a situation where environmental policies should have not only environmental but also human effects “central to planning”.

Therefore, it is the attitudes that most people hold of the public transport system that limit not only its usage but also its improvement. If the people that use it are mostly from certain groups, which do not possess the ability to suggest changes which are significant, then change becomes impossible. It is only when the wider public is also involved in the process of implementation and feedback, that a system improves.

There seems to be a certain stigma present in a specific section of Bahraini society, a section perhaps filled with mostly individuals in prosperous positions, of using the red bus system: a valuable public good rightly provided by the government signifying a step in the proper direction. One would think with the recent implementation of better and cleaner buses alongside an accessible information system, this stigma would be removed.

Much like how the London public transport system is one used by the masses, with passengers being the young bankers off to work or stay-at-home moms off to the park or students off to school, the Bahraini red bus system also needs to adapt. Specifically, it is its perception within the wider public that needs to adapt, from a good mostly utilised by certain groups to a good that indicates a modern outlook, a concern for the environment and a solution to congestion.

If it were indeed a system used by the masses, then these masses would not only include certain groups, but rather that all groups of society would utilise a valuable public resource which has numerous benefits towards the economy and environment.

Whether the reason for a stigma is issues that people hold with the red bus system itself or a societal stigma on using public transport based on status, we do not know. It is accepted that for perceptions to change, incentives have to change as well. The recent increase in petrol prices alongside a removal in the government subsidy would indicate a move towards other modes of transport. However, since specific research is almost non-existent, this makes it hard to investigate the actual correlation between this price increase and public transport participation.

Conversely, what is available is research on successful public transport systems implemented in other parts of the world. One particularly interesting case-study on public transport was

Page 2

the Temuco Te Mueve Public Transport Plan implemented in the Chilean city of Padre Las Casas. What makes this study interesting is that it involved a clear link between the communities that were going to use the system and the institutions developing the system itself. There were “close encounters between regional transport staff and grassroots neighbourhood associations”[2]; it was this dynamic of “permanent citizen-government collaboration” which facilitated the program’s success. The same type of collaboration, if implemented in Bahrain, could garner the same effects; it facilitates dialogue between citizens and transport planners. As stated earlier, in order for the dialogue to be possible participation within the system must exist throughout all actors within the economy, however at the same time the government’s role must be to ensure that this participation leads to “genuine transformation of the final product,” i.e. acting on the demands of the masses and addressing the concerns that come up.

Another key innovation that the Temuco project introduced was the Danish Innovation Laboratory’s reverse traffic pyramid which put “cars at the bottom and pedestrians, cyclists and public transport at the top of a new set of priorities for urban and regional transport systems”. This changing of incentives signals clear and bold prioritisation for public transport, changing attitudes and nudging individuals towards other modes of transport. Overall, the main takeaway from the Temuco project for the Bahraini government should be that an effective public transport system was developed by “creating a roundtable that brought institutional actors together…with citizen organisations”; a system built upon the process of direct feedback and interaction.

As stated before, macroeconomic decisions as important as public transportation which affect the environment, economic agents, and the wider economy require a more nuanced approach. Some of this nuance can be in recognising that the social interactions people have with transportation itself are important in how a system is developed. As seen, there does exist some type of psychological or societal decision in people’s minds when choosing to use public transport in Bahrain or not. Yes, there are economic factors such as the ease of travelling by car whenever most suitable to the individual, the lack of bus stops near corporate workplaces, and other practical considerations. However, if practicality were the only reason for not using public transport, then these issues would be voiced not only by the individuals using the red bus system, but also potential users from every part of society who are invested in it. This is why the reason for limited usage of the red bus system cannot be as clear-cut as highlighting issues like late buses, the sparseness of bus stops, inconsistency, or an ineffective pricing system. All of these issues have the assumption that individuals are rational actors within the economy with rational demands central to them not using the bus.

To uncover some of the reasons behind why people might not use public transport, we will first look at the rudimentary-level, conventional economic analysis and then progress onto some more nuanced and unorthodox analysis

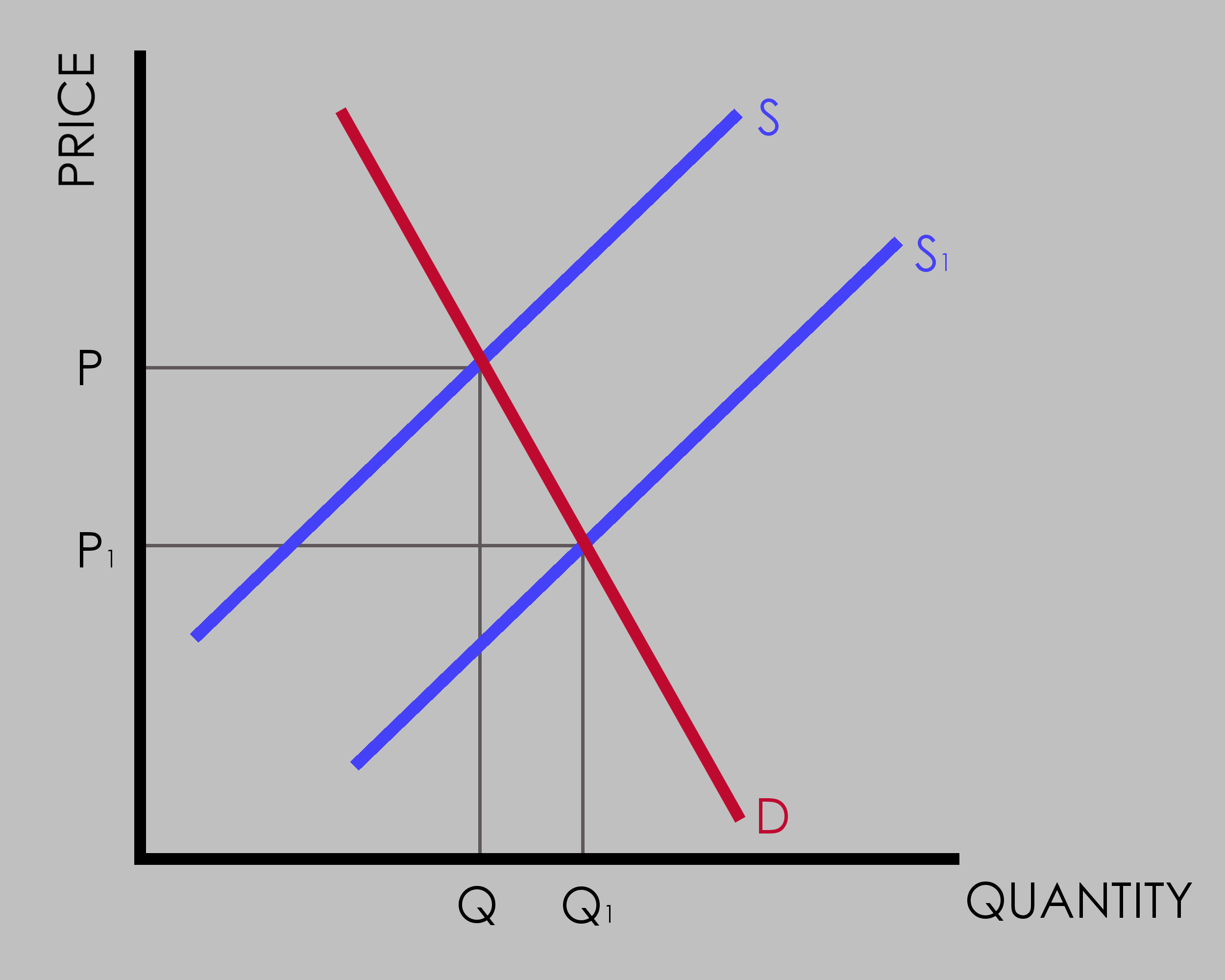

One reason that often presents itself as a barrier to using public transport is the price. As is often the case, this can result in the government subsidising it. A rudimentary-level economic analysis of the situation reveals that if public transport were to be subsidised, the result would not be favourable. On the one hand, the cost for the consumer is reduced, allowing economic activity to be more easily facilitated than before; individuals for whom the cost of public transport hindered their mobility, it now becomes easier for them to travel. At the same time, as public

transportation appears to be cheaper than before, it also becomes more attractive than before in comparison to other forms of transport; the classic substitution effect.

A subsidy applied on Transportation when demand is elastic

However, findings by the Transport Research Laboratory, an independent transport consultancy, in its extremely comprehensive 2004 report into the demand for transport found that public transport had inelastic demand in the short-run. Signifying the recent surge of car ownership, this shows that inelastic demand coupled with a government subsidy would not have much of an effect. Although, it was also seen in the report that in the long-run elasticities seem to increase for separate transports [3].

A subsidy applied on Transportation when Demand is Inelastic

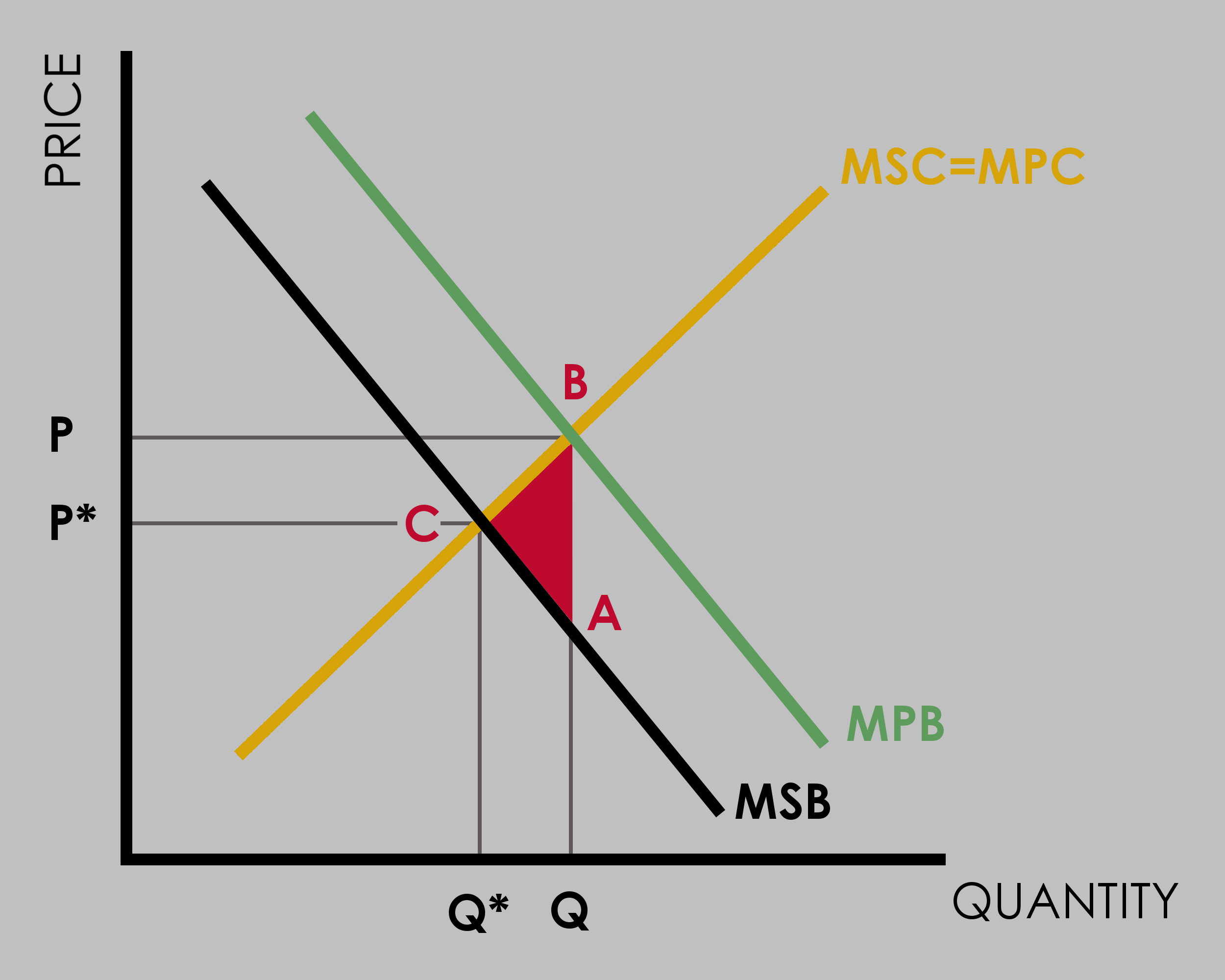

Going into the market failure scenarios, certain externalities also appear when looking at public transportation and its alternatives. The current situation in Bahrain is one in which most individuals are car owners and the levels of air pollution that increase are indirect costs to third parties; in this case, the third parties would perhaps be the individuals who are using public transportation or ones with no car. The full social benefit of using cars over public transport is lower than the private benefit. Therefore, a welfare loss occurs at ABC where there is evident overconsumption and overproduction.

Page 3

Negative Consumption Externality

If society were to move towards public transport, perhaps the welfare loss would be removed as the production and consumption of cars were to decrease.

Continuing with the different scenarios of market failure, there is also a positive consumption externality associated with public transportation that is being missed out. The use of public transport eases congestion on roads and also contributes towards lowering air pollution levels; these are positive spillover effects for third parties that are not directly using public transport. However, given that current consumer participation within the public transport system is not as high as preferred, there exists a welfare loss of ABC. This is the loss of potential gains that could have been made if widespread use of public transportation existed; an underproduction and under-consumption of the resource have led to allocative inefficiency within the macroeconomy.

Positive Consumption Externality from Public Transportation

However, the arguments given above follow the classic, orthodox, rudimentary-level economic analysis of the public transport system. Although most of the analysis currently in the realm of transportation economics and policy circles involves the use of far more rigorous and complex models than the ones above, they all operate on the simple assumption of rationality that has come to dominate most economic reasoning.

In a shift away from that assumption, a laboratory experiment undertaken by Sunitiyoso, Avineri and Chatterjee (2010), looking at the effect of social interactions on travel behaviour stood out. It stood out because of its relevance to the argument of this essay: how the Bahraini bus system’s limited range of users is directly linked to their perceptions of the Bahraini bus system's.

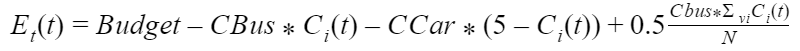

The game is set up in such a way that the goal is to reduce car use. A hypothetical employer is introduced with employees (participants) given a budget for transport expenses, covering car and bus usage. Depending on the collective bus-use of the employees, i.e. the number of weeks per month that the bus is used, a reward is made. The reward is half of the total expenses that were spent on the collective bus-use, with it being equally distributed among all participants, whether they used the bus or not [4].

With a clear payoff function being formulated as:

Ei(t) being the total sum obtained by individual i at a time period t. Budget is the fixed amount of money given to spend on transport expenses each month. CBus and CCar are the costs of using the bus and car, respectively. Ci(t) is individual i’s choice i.e. the number of weeks per month that he/she uses the bus, and N being the number of employees (participants) [i].

In this particular game, the cost of using the bus was kept higher than using a car, meaning that for an isolated participant, using the car represented a higher payoff. However, if all individuals in the group cooperated and used the bus, there would an even higher payoff. Although these payoffs were calculated using transportation costs in England, they also have something to contribute to our analysis. The payoffs show that collective bus-use ends up as being most beneficial to everyone; while individually using the bus represents a higher cost, collectively it does not.

This could be linked to a ‘tragedy of the commons’ argument. Given that air in Bahrain is a resource freely available to all, it results in a negative production externality. The mass-production of cars (and other air-damaging products, but for argument’s sake we will consider only cars) only takes into account the private costs of production (e.g. the cost of design and assembly, marketing, sales, etc.). It chooses to ignore the widespread social costs of increasing pollution levels or driving demand for petrol (a fossil fuel). As a result, an overproduction and over-consumption of the resource exist. Therefore, perhaps, the low cost of using a car is because it chooses to ignore the social costs of pollution. Whereas, a higher cost of using the bus is perhaps because it represents a move towards the socially optimal equilibrium, thereby drawing a higher price.

Tragedy of the Commons, example, Air

Page 4

The added feature within the game was also the fact that throughout it participants could ‘interact’ with each other through an anonymous messaging service within the system. A hypothesis was set up to test whether this interaction influenced the behaviour of individuals either by reinforcing or changing the original decision [ii]. Through some ANOVA analysis, goodness-of-fit tests, and the use of learning models a conclusion was reached. It was found that that there were indeed “strategic behaviours that follow social learning models of confirmation…and conformity”; in other words, decisions were reinforced or changed when interacting. Once individuals became aware of the other’s perceptions or decision to take either the bus or car, attitudes changed. Furthermore, Bartle and Avineri (2007) also find that if face-to-face communication is introduced it “would have a greater influence on individuals’ behaviour” [5].

What this research hints at is that herding behaviour or at least a strengthening of attitudes is involved when looking at transportation systems. If attitudes have been formed of a certain transport system by a few individuals, then these attitudes can influence others. Whether the payoff was crucial in these lab decisions or not, we do not know. However, even if it was, following decisions may not have even considered the payoff; they may have simply considered the actions of other individuals.

Much like how the participants in the game were somewhat influenced by the actions and behaviours of others when choosing their mode of transportation, this suggests that perhaps the solution to the Bahraini red bus system is not embedded in increasing investment into it or improving schedule consistency. If social interactions are indeed important in transportation decisions and these interactions can change behaviours, perhaps it is only a simple changing of attitudes within the minds of Bahrain’s residents that need to take place. Further improvements like the ones mentioned above will only serve to become a byproduct of that change in attitude, through the process of outspoken feedback.

Public transport might not be the most pressing or even the most interesting topic to talk about. However, what the public transport issue signifies is a clear revelation of how intrinsic attitudes can shape the decisions individuals take within the economy. These attitudes, more often than not, can also be rooted in mistaken assumptions, made by economic agents without any basis of fact or evidence. And instead of mainly delving into the complex analysis of whether incentives are properly aligning or investigating and analysing the different data-sets that economic agents have to offer us, perhaps it is only a simple matter of changing abstract concepts, like the perceptions or attitudes within people’s minds.

i The premise of this game and its mathematical modelling is taken directly from Sunitiyoso, Avineri and Chatterjee’s (2010) paper looking at the specific role of social interactions on travel behaviour.

ii Again, the hypothesis is also one of the three main hypotheses that Sunitiyoso, Avineri and Chatterjee develop in their paper when looking at the experimental treatments; they also recognise the prevalence of conformity models; Henrich and Boyd, 1998; Kameda and Nakanishi, 2002; Smith and Bell, 1994

SOURCES

1 State of the Environment in the Kingdom of Bahrain. Report. Kingdom of Bahrain Public Commission for the Protection of Marine Resources, Environment and Wildlife, 2009

2 Sagaris, Lake. "Citizen Participation for Sustainable Transport: Lessons for Change from Santiago and Temuco, Chile." Research in Transportation Economics 67 (May 2018). Accessed June 19, 2018.

3 Balcombe, Richard. The Demand for Public Transport: A Practical Guide. Report. Transport Research Laboratory. Accessed June 20, 2018.

4 Sunitiyoso, Yos, Erel Avineri, and Kiron Chatterjee. "The Effect of Social Interactions on Travel Behaviour: An Exploratory Study Using a Laboratory Experiment." Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 45, no. 4 (2011): 332-44. Accessed June 20, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.tra.2011.01.005.

5 Bartle, Caroline and Erel Avineri “Pro-social behaviour in transport social dilemmas: A review.” In Proceedings of the workshop of frontiers in transportation: social interactions, Amsterdam, 2007

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Hussain Abbas is currently an economics undergraduate at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). Born in Pakistan, he has lived in Bahrain for over fourteen years.

Contact Details:

Email: h.abbas1@lse.ac.uk

twitter: @hussain2853