This article was co-authored by Engy Abdelnasser and Baland Al Rabayah

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the most significant crises for the global economy. The pandemic had created a situation where nearly most aspects of society had faced a standstill in traditional forms of interactions. The consequences are that multiple sections of society had to suddenly adapt to unexpected conditions of the pandemic. In particular, this article will look at how the education sector in Bahrain adapted to the new challenges brought upon by the pandemic.

First, we will discuss how government education policy and education sectors respond to subsequent lockdowns. Second, we will then look at the outcomes of such responses based on students' satisfaction and concerns. Last, we look at the implications of such outcomes and recommend policies.

Approaches taken during the lockdown and their outcomes

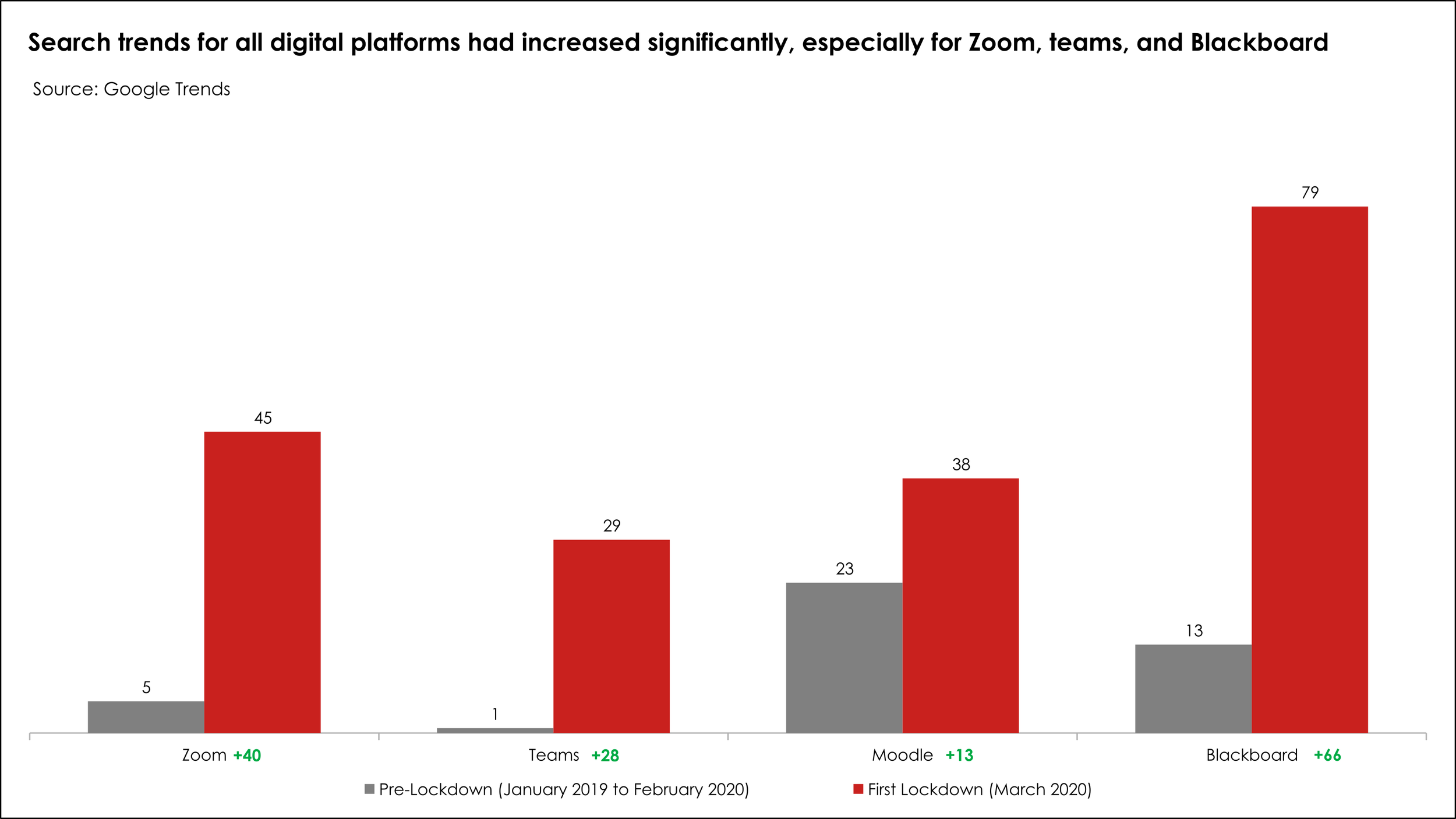

During the lockdown, the government and education institutions had taken two different approaches: implementing digital mitigation solutions and “traditional” mitigation solutions. We first start with digital solutions. Education institutions have begun using digital classrooms like blackboard, moodle, zoom, and Microsoft teams as their primary method of conducting classes and forms of communication with students. Although these platforms were not necessarily new towards educational institutions, their usage was only secondary for educational purposes. This is also reflected by supporting data of increases in zoom searches on Google, indicating that education institutions (and workplace) had attempted to respond by mitigating towards these digital platforms quickly:

In all cases, we see a significant jump between pre-lockdown search trends and the announcement of the “first-lockdown.” This trend is also seen with the extension announcement for “back to class” sessions in September 2020 (1). Another policy that the government and education institutions had implemented was moving exams online.

Our second area of discussion is that of “traditional” solutions implemented. The government broadcasted 238 courses on Youtube, with 383 courses also broadcasted on TV. Additionally, eight-hour lessons on TV in Both English and Arabic were provided (2). Furthermore, the government had also planned to ease the pressure off students during the pandemic by providing “lines” that students can address questions. Moreover, the government had also implemented three different virtual channels to allow educators to reach out to students (3).

Overall, what are the outcomes of the responses towards the pandemic? Although no data is known to the author to support that these measures had a “positive impact” on student achievement and human capital outcomes, we should argue that these responses had averted potentially even further adverse outcomes. First, we should mention that students’ satisfaction with education outcomes has been negatively affected. This includes concerns that students had little chance of engagement and that online exams had relatively little time to answer questions. Furthermore, there were also concerns about how online learning solutions cannot capture body language, given that students had their cameras off. Last, we should also mention that not all forms of learning (such as practical hands-on learning experiences) cannot be replaced by online classes in full.

Mentioning these concerns voiced by students and other key stakeholders, we return to the central argument behind the outcomes of the responses. Take a hypothetical scenario that little to no response had been carried out by the government and the education industry as a whole, or that response roll-out had been significantly longer than seen. The likely outcomes are that little to no learning would have been achieved throughout the so-far seen duration of the pandemic (or delayed implementation of learning), which would have even further reduced human capital outcomes for students. Therefore, it is likely that responses towards the pandemic implemented by the government and education industry had mitigated some of the declines in students’ human capital accumulation compared to the “no-intervention” or “slow-intervention” scenarios. For example, we could graph the difference between “no-COVID,” “intervention,” and “no-intervention” accumulation of human capital for students over time in the graph below:

Although these short-term government interventions are likely to offset some of the declines in human capital accumulation of students, they are unlikely to fully mitigate the full extent, given that such an intervention is likely to be imperfect. In the next section, we discuss the implications and recommended policies.

Policy Recommendations and implications of the current trends

Given that the government and education sector had taken the most appropriate short-term interventions, if we account for the unprecedented challenge they were faced with, we should discuss the implications of the likely current trajectory and the recommended policies. As for students' human capital growth trajectory, we will likely see that human capital will be lower than if COVID did not occur. Furthermore, experts in the field had voiced their concerns that transitioning towards remote learning is likely to worsen the learning gap, especially between affluent children and that less-well-off (4). If left unchecked, this will have some long-term impacts on productivity levels of the economy and the welfare of students affected by the events of COVID-19.

Therefore, the most appropriate policy is to look at long-term investments into bringing human-capital accumulation back into its trajectory. Assume a hypothetical scenario where the government and education sector take long-term initiatives; we can compare our three scenarios towards our “no COVID” scenario, being “short+long term intervention,” “short-term intervention,” and “no-intervention.”

The potential long-term interventions which the government can take are an increased amount of targeted educational interventions for skills that are likely to be most affected during COVID periods that require remote learning. This is particularly important for skills that need “hands-on” lessons and classes. Therefore, the key policy recommendation is to identify skills that are most likely to be severely affected by remote learning and COVID-19 short-term education responses and implement wide-scale targeted educational training post-COVID for students who are likely most affected for voluntary retraining in those skills.

conlusion

We see that the government and education sector had taken swift action to combat the effects of the pandemic on education. These actions were broken down into digital responses and traditional solutions to continue education in the Kingdom. Although imperfect, as given by the students' accounts, the likely outcome is that the intervention and responses towards the pandemic will likely offset some of the declines in human capital outcomes. However, our policy recommendation is that more long-term interventions such as targeted training of skills that are likely affected by the pandemic for students are recommended to ensure that human capital outcomes reach their intended trajectory levels.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

SOURCES

(1) Mansoor: Bahrain postpones reopening of public schools by two weeks (2020)

(2) Bahrain turns to e-learning amid Covid-19 pandemic. Oxford Business Group. (2020, December 21). https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/news/bahrain-turns-e-learning-amid-covid-19-pandemic.

(3) Ibid.

(4) Corral, Dehnen, and D’Souza (2021), Accumulation Interrupted? COVID-19 and Human Capital

(O5) Google Trends

Engy Abdelnasser is a graduate of the American University in Cairo with a double major in Communication and Media Arts and Political Science. Engy is currently studying Refugee Protection and Forced Migration Studies at School of Advanced Study, University of London. Engy is passionate about volunteering for different causes like environmental and social causes.

email: e.abdelnasser@bhres.group